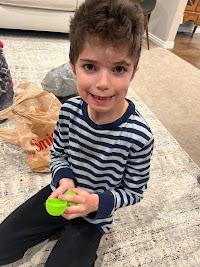

Samuel and Jonathan; a tale of two asphyxiations

Even though he is eight years old, my son Samuel, who has

autism and epilepsy, needs a baby monitor beside him through the night. This monitor is not here to alert us to when

he wakes up, but to alert us to when he has a grand mal seizure, and is in

danger of choking to death on his own saliva and bile. My job, when I hear a noise akin to the

Nazgul from Lord of the Rings on the monitor, is to jump out of bed, run to his

room, and make sure he is propped up or on his side and that his mouth is clear

of anything he can choke on. I then hold

my convulsing son until the seizure has passed.

Typically, these only happen every month or two, but they have begun

getting more frequent.

Our 6-year old, Jonathan, was born with a weak respiratory

system. The day he was born, his lungs

needed to be sucked out and he had trouble breathing. Every doctor we’ve seen, traditional and

holistic, has tried to tell us that his throat and lungs are fine, but we KNOW

that is not the case. Whenever he gets

even a minor cold, his lungs close and he can’t breathe any longer. We have been to the hospital many times hoping

the doctors can do something to open his lungs in these emergency situations,

only to find that they can do little more than what we could do at home. We have found that the best thing we can do

for him is to wrap him up in some blankets, and put him outside in the freezing

cold air where the cold can help reduce the inflammation in his lungs, then

hook him up to a nebulizer and watch him suffer, struggling to breathe, sometimes

for days at a time.

This morning was the perfect storm. At 5:50am, I woke up to that familiar noise

from the baby monitor. This is the

second night in a row Samuel has had a grand mal seizure. I jumped out of bed to run to his room to ensure

he was positioned in a way that he wouldn’t choke to death, when, in the

hallway, my son Jonathan was awake and in distress. He couldn’t breathe, and was worried he was

choking to death. In the background, my

daughter was crying, having been startled awake from Jonathan panicking.

Samuel was priority one.

In less words, I told Jonathan he was just going to have to choke for a

couple minutes, and dashed into Samuel’s room.

He had retched bile and was covered in it while his whole body was

convulsing. I propped him up as I had

done so many times, pried his clenched mouth open as best I could, and cleared

his airway, then held him still until the convulsions stopped. Fortunately for Samuel, these always happen

in his sleep and he has literally NEVER had a recollection of one of these

seizures, so while it is hell for us, he is wonderfully oblivious to what just

happened to him. Once the convulsions

stop, he’s still asleep, so I lay him back down on his bed and decide I’ll

clean up the mess of bile later.

I then take Jonathan, who is clearly hyperventilating in

addition to having trouble breathing, and throw him outside in the 20-degree

weather. I get a bunch of blankets and

hot packs to wrap him up in to keep him warm, and tell him to work his best on

taking deep breaths of the cold air. (Side note: I am doing all of this in my underwear, however,

having woken up with a burst of adrenaline, I can’t feel how frigid it is).

Once my two sons are stabilized and I know neither of them

will die at any moment, I move on to my 3-year-old daughter, who is in tears as

she just watched her dad run back and forth trying to stop her two older

brothers from choking to death.

Once she is marginally consoled, I work through the morning

routine: I let the dogs out to pee, get dressed, feed the dogs, make breakfast

for the kids, change the baby’s diaper, change the 8-year-old’s diaper, clean

the bile off his sheets, take out the trash, empty the dishwasher, and

periodically check on my son outside who is still in distress, but at least he

isn’t dying.

These “normal” morning routine activities are the hardest. I was just jolted awake as if being

electrocuted, and leapt into a warzone.

I was jacked on adrenaline as my whole focus was preventing my kids from

dying. Then, once that adrenaline wears

off, I am left, mentally and physically exhausted, just having experienced an

intense trauma, and I have no time to rest or meditate. I still have to do all the daily routine as

if I had just woken up to sunshine and rainbows. Meanwhile, my hands are shaking while I cook

eggs, my heart is aching while I clean Samuel’s sheets, and my mind and body feels

completely broken while I change the baby’s diaper.

Days like these happen far too often, however, there is

still much to be grateful for. My mom

used to always say, “it’s amazing what someone can do when they have to.” I am grateful that despite being so broken at

the end of one of these episodes, I can rest assured that I have the capacity

to endure the situation. I am grateful

for my wife who is so much stronger than me when dealing with these things, and

who is so faithful and supportive. I’m grateful

for all the family and friends I have, who surround us with support while we

endure these things. And most of all, I’m

grateful for Jesus Christ, who has experienced EVERYTHING I am experiencing and

more. I know that my suffering will help

me better understand Him, and that through my sorrow, I can become more like Him.

I am grateful for this morning. It was hard, and I wouldn’t have had it any

other way.

Comments

Post a Comment